The GI-MAP (Gastrointestinal Microbial Assay Plus) test is a helpful tool for understanding what’s happening in your gut. It examines the DNA of microbes in your stool sample to identify and quantify them.

In addition to DNA analysis, the test checks markers for immune function and digestive proteins. Abnormal levels of these proteins may signal issues like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Another feature of the GI MAP is that it indicates if you are resistant to certain antibiotics. This information may be helpful when treating you for certain infections.

The GI-MAP test benefits individuals experiencing persistent digestive discomfort or irregular bowel habits or those who want to take a proactive approach to their health. If you’ve been grappling with unexplained symptoms like bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain, or changes in bowel movements, the test can provide clarity. Additionally, anyone curious about their gut health and its potential impact on overall well-being can benefit from the insights offered by the GI-MAP report.

This article provides insight into how to read your GI MAP reports, the clinical implications of identified microorganisms, and the clinical significance of the markers.

How To Interpret Your GI MAP Reports

The GI MAP report is in tabular form. The first row consists of the following (from left to right): the microorganisms or marker, followed by the result, then the reference.

The results could be the number of microbes per gram of stool. For example, 3.5 e7 is equivalent to 3.5 × 107 of a particular microorganism in a gram of stool. A result could also be “Detected,” “Not Detected,” “Absent,” or “Present.”

Your GI MAP report will show your result compared to normal values (reference). The value will be in red if you have an abnormally high result for a microbe or marker. If the result is low, it will be in yellow.

- <dl means the result is below the detectable limit.

- >dl means the result is above the detectable limit

- N/A represents “not applicable.”

The following section will enlighten you about the characteristics of gut microbes in the GI MAP panel and the possible clinical implications when the results are outside the standard limit.

Understanding the Pathogens in Your GI MAP Report

Pathogens are microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that can cause disease in humans.

Bacteria Pathogens

Bacterial infections are often transmitted through contaminated food and water, which may contain fecal materials. If you find a pathogen in your GI-MAP report, it’s important to note that this alone doesn’t necessarily mean you have a disease. Instead of immediately taking antibiotics, consider hydrating well and incorporating probiotics to support your gut-immune system.

Discussing the results with your healthcare provider, who will consider any clinical symptoms you might be experiencing to make an accurate diagnosis based on the comprehensive picture presented in the report, is vital.

Clostridium difficile

This pathogen is known for causing mild to moderate diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and frequent belching. It often affects individuals who have been on antibiotics for an extended period. It is a common hospital-acquired infection in about 20% of hospitalized patients. This organism releases toxins A and B, which cause inflammation and damage the gut lining.

Escherichia coli

E. coli is a diverse bacterial species found in humans and animals and can spread through contaminated water, food, or contact with infected individuals. While some strains are harmless, six pathogenic strains can cause various infections, such as traveler’s diarrhea, childhood diarrhea, dysentery, hemorrhagic colitis, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. The O157:H7 type is prevalent worldwide and implicated in many outbreaks of bloody diarrhea.

Certain types of E. coli, particularly those producing heat-labile toxin (LT) and heat-stable toxin (ST), can cause diarrhea. Another variant, Shiga-like toxin (stx1 and stx2) producing E. coli (STEC), is linked to foodborne outbreaks causing gastrointestinal illnesses, including bloody and non-bloody diarrhea.

Salmonella

Salmonella is a common cause of foodborne illness. It’s a major health concern, causing gastroenteritis with symptoms like fever and severe diarrhea. Fortunately, most cases are resolved within a week. However, antibiotics may be necessary if the infection gets into the bloodstream.

Vibrio cholerae

This pathogen is also transmitted by fecal contamination of ingested foods. While it may be asymptomatic, a severe infection can manifest with watery diarrhea, vomiting, thirst, and irritability.

Yersinia enterocolitica

Similar to Vibrio cholerae, this pathogen is associated with food poisoning, presenting symptoms such as vomiting, fever, bloody diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

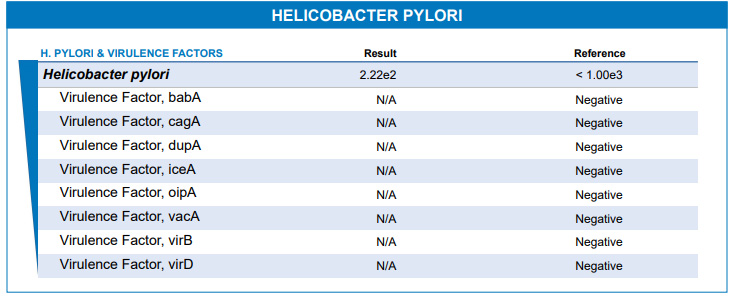

Helicobacter pylori

This bacteria is notorious for causing gut ulcers. Some cases don’t show symptoms and might not need treatment. Still, when H. pylori carries harmful genes, it can signal potential issues, helping doctors decide if treatment is necessary. Examples of H. pylori’s harmful genes featured in the GI MAP include babA, cagA, dupA, iceA, oipA, vacA, virB, and virD. CagA and vacA in high quantities are known to increase the risk of developing a disease from H. pylori infection. In contrast, the other genes are markers of the severity of the infection.

Parasitic pathogens

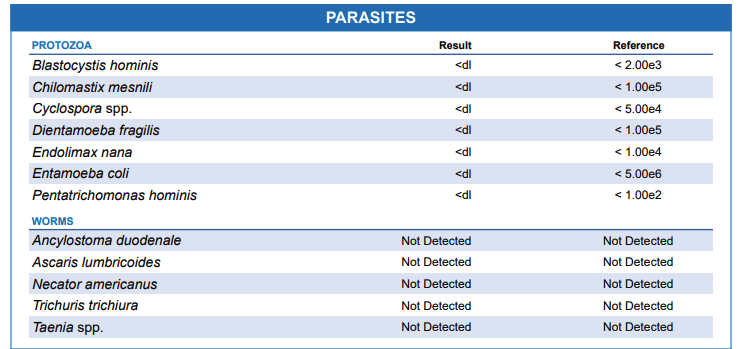

Parasitic pathogens are organisms that live off our nutrients without offering any benefit. They can cause infectious diseases with symptoms like loose stools and abdominal pain. Transmission occurs through contaminated food, water, or poor hygiene. Tailored treatments targeting specific parasites are essential, and you must undergo post-treatment testing to ensure complete eradication. A standard GI-MAP report features the following parasitic pathogens:

Cryptosporidium

This parasite is transmitted in swimming pools. Cryptosporidium can bring about symptoms such as gas bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. In a person with a strong immune system, this infection typically resolves on its own within 2–3 weeks.

Entamoeba histolytica

This parasite commonly infects those who live in or travel to tropical regions with poor sanitary conditions. It spreads through contaminated surfaces or food and may not make you sick. If you do get symptoms, they’re usually mild, like abdominal cramps and the passage of loose stools. In some cases, it can infect your liver or even spread to the lungs and brain, but that’s not common.

Giardia intestinalis

It is a widespread parasite found in outdoor water sources such as lakes and commonly infects daycare workers. It can manifest with symptoms ranging from diarrhea to bloating and weight loss. It can also cause sleep disorders and depression. You must be aware of the risks of being infected by this parasite if you spend time in outdoor water.

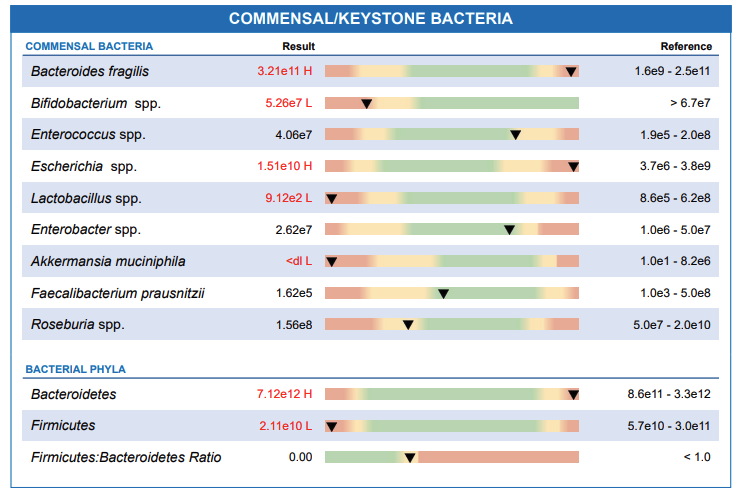

Commensal/Keystone Pathogens

These friendly pathogens, called commensal bacteria, do beneficial jobs in our guts. They extract nutrients and energy from our food, keep our gut strong, make essential vitamins like biotin and vitamin K, and even stand guard to keep out harmful pathogens.

The GI MAP report features commensal bacteria like Bacteroides fragilis, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. If there are too many commensal bacteria, it could mean there’s an ongoing infection in your gut. On the flip side, if they are too few, your gut has a reduced capacity to withstand harmful pathogens.

There is an exception to the rule. Some commensal bacteria are only beneficial in the gut but could become harmful when they escape into the bloodstream. They are classified in the GI MAP report as commensal-inflammatory and autoimmune-related bacteria. Examples of such microbes include Enterobacter, Escherichia, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella. They can cause diseases such as arthritis (inflammation of the joints), spondylitis (inflammation of the spine), and other autoimmune diseases.

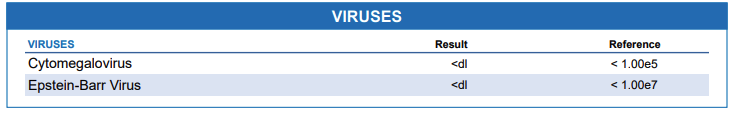

Viral Pathogens

Your GI-MAP report may include viral pathogens such as Adenovirus, Norovirus, Cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. These viruses are often associated with diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. While these infections typically resolve on their own, it’s crucial to recognize them as potential contributors to gastrointestinal issues. Adenovirus is a prevalent cause of diarrhea in infants and children, whereas Norovirus is more common among adults. Cytomegalovirus has been implicated as a cause of some respiratory illnesses. Epstein-Barr virus has also been found to be capable of stimulating the immune system against our tissues.

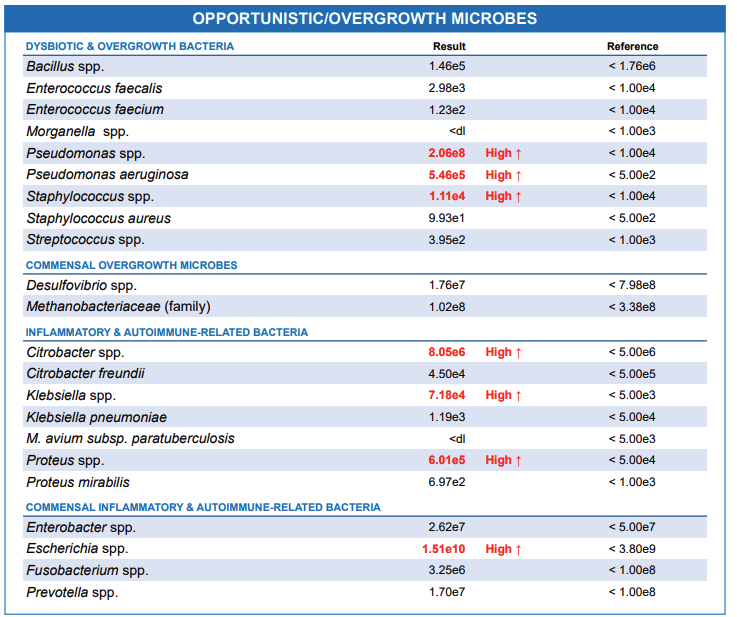

Opportunistic Pathogens

Some bacteria in the GI MAP report are opportunistic pathogens because they only pose a threat when your immune system is weak. They can also overgrow if the beneficial bacteria in your gut are compromised by poor diet, prolonged antibiotic use, or parasitic infection.

Some opportunistic pathogens, including Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Mycobacterium, can breach the gut wall, enter the bloodstream, and imitate our body cells. This confusion can lead our immune system to attack our tissues.

Other opportunistic pathogens you can find on your GI MAP report include the microbes that cause damage by overgrowing, e.g., pseudomonas, bacillus, streptococcus, staphylococcus, and Morganella.

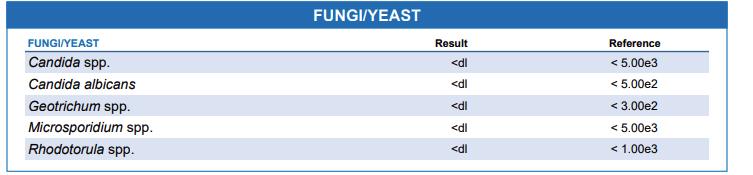

Fungal Pathogens

Fungi are a normal part of our digestive system, but if they grow too much, they can cause problems in our gut. Signs of fungal overgrowth might include bloating, constipation, diarrhea, and conditions like athlete’s foot or yeast infections. The GI-MAP test can help spot fungi like Candida, Microsporidia, Geotrichum, and Rhodotorula. Managing fungal overgrowth involves taking a diet low in sugars and starches; sometimes, medication is needed.

Worms

When checking for worms on your GI-MAP report, you’ll get a result of either “Detected” or “Not Detected.” If it’s “Detected,” it means there’s a significant amount of worm DNA, possibly from an adult worm or eggs. If it’s “Not Detected,” it means no or very low levels of worm DNA were found, which are often harmless, as tiny amounts can naturally be in your gut from food or water.

Ascaris lumbricoides

Ascaris lumbricoides is a common gut roundworm that spreads through contaminated food and water. It often infects people without any noticeable signs, but some may experience respiratory symptoms such as cough during the early stage. As the infection progresses, it can lead to abdominal problems such as pain, nausea, vomiting, and more severe conditions like appendicitis.

Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator Americanus

They are roundworms that enter the body by penetrating the skin. Suppose you get infected by any of these two; you may experience early symptoms such as itching and rash in the area where the worm penetrated your skin. Severe infection may lead to abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, weight loss, and blood loss from the part of the intestine they invade.

Trichuris Trichiura (Whip worm)

This worm finds its way to the gut through contaminated food and water. Individuals infected by this worm rarely manifest any symptoms. However, some individuals may experience diarrhea with the passage of mucus and blood.

Taenia solium

This parasite is commonly referred to as a tapeworm. It is usually contracted through the consumption of undercooked pork or beef. Infections typically involve a single tapeworm, which may cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, weakness, and more.

Protozoan Parasites

This group of parasites is non-pathogenic because they are present in the gut but do not cause illness. Examples of protozoan parasites featured in the GI map include Blastocystis hominis, Chilomastix mesnili, Cyclospora, Dientamoeba fragilis, Endolimax nana, Entamoeba coli and Pentatrichomonas hominis.

Understanding The Markers in Your GI MAP Report

The markers on the GI MAP report were chosen for their practical use in understanding your overall health beyond gut health alone.

Steatocrit

Steatocrit is a measure of the fat percentage in your faeces, indicating how your gut processes fat. High levels (>15%) could suggest issues like maldigestion or malabsorption. Low stomach acid and poor digestion can also contribute to elevated steatocrit.

Elastase-1

Elastase 1 is a helpful marker that gives insights into your pancreas’s efficiency in breaking down proteins. If it is extremely low, it could indicate challenges with digestion or inflammation (pancreatitis).

Beta glucuronidase

Beta-glucuronidase is an enzyme naturally produced by gut, liver, and kidney cells. While it plays a crucial role in detoxification, elevated levels of this enzyme can break down harmful substances, potentially increasing the risk of certain cancers. Research has associated high levels of beta-glucuronidase with an increased risk of cancer in the gut.

Calprotectin

This marker is a reflection of the activity of the immune system in your gut. It is often elevated when there is an ongoing gut infection or inflammatory bowel disease.

Occult blood FIT (Fecal Immunochemical Testing)

This marker is the measure of the amount of blood in your stool. Examples of conditions where it can be abnormally high include bleeding ulcers in the gut, cancers, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Secretory IgA and Anti-gliadin antibodies

Secretory IgA protects the gut from organisms that could breach the wall and enter the bloodstream. Elevated levels of IgA may indicate an ongoing immune response to a gut infection. Anti-gliadin antibodies indicate an immune response against a gluten diet. A high anti-gliadin antibody in the stool sample suggests that you should avoid a gluten diet.

Zonulin

Zonulin is a protein in our gut that controls the openings between cells in the gut wall, called tight junctions. These junctions can open or close based on the body’s needs. Zonulin opens these junctions, especially when dealing with infections, to help flush out bacteria and toxins.

When these tight junctions don’t work properly, it can lead to a condition known as “leaky gut,” where substances from the gut pass into the bloodstream. This leaky gut has been linked to various health issues like inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, food allergies, irritable bowel syndrome, and more.

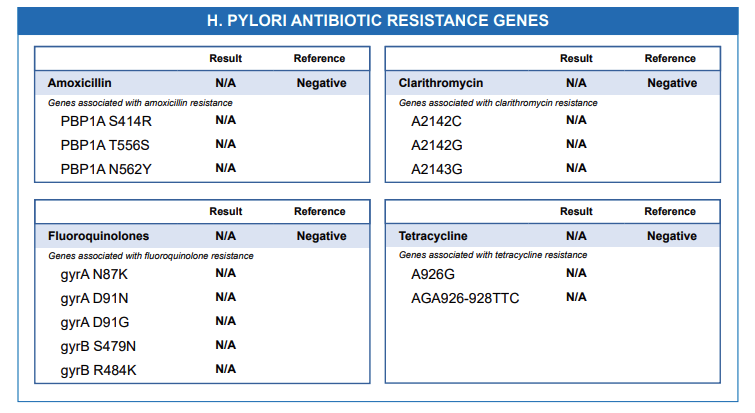

Antibiotic Resistance Genes

The GI-MAP test examines genes in your gut microbes that make them resistant to specific antibiotics. If a resistance gene is detected for a particular antibiotic,it is labelled “present” on the report, and it indicates that this antibiotic may not be the most effective choice for treatment. For instance, H. pylori infection is usually treated with antibiotics like Amoxicillin, Clarithromycin, Fluoroquinolones, or Tetracycline. Suppose the strain of H. pylori in your stool sample carries the A2142C gene. In that case, it means the microorganism is resistant to Clarithromycin, making it unsuitable for treatment in this case. The same applies to other antibiotics featured on the GI map report, e.g., sulfonamides, trimethoprim, chloramphenicol, macrolides, beta-lactams, and vancomycin.

Common drugs that are fluoroquinolones include Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin. Beta lactams are penicillins and cephalosporins. Examples of macrolides are Azithromycin and Erythromycin.

While the GI-MAP test is a powerful tool for gaining insights into your gut health, it’s crucial to recognize that the report it generates is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The information provided in the report should be viewed as complementary to, rather than a replacement for, the guidance of a healthcare professional.

You can find a sample pdf report here. Image credits: DiagnosticSolutionLabs.